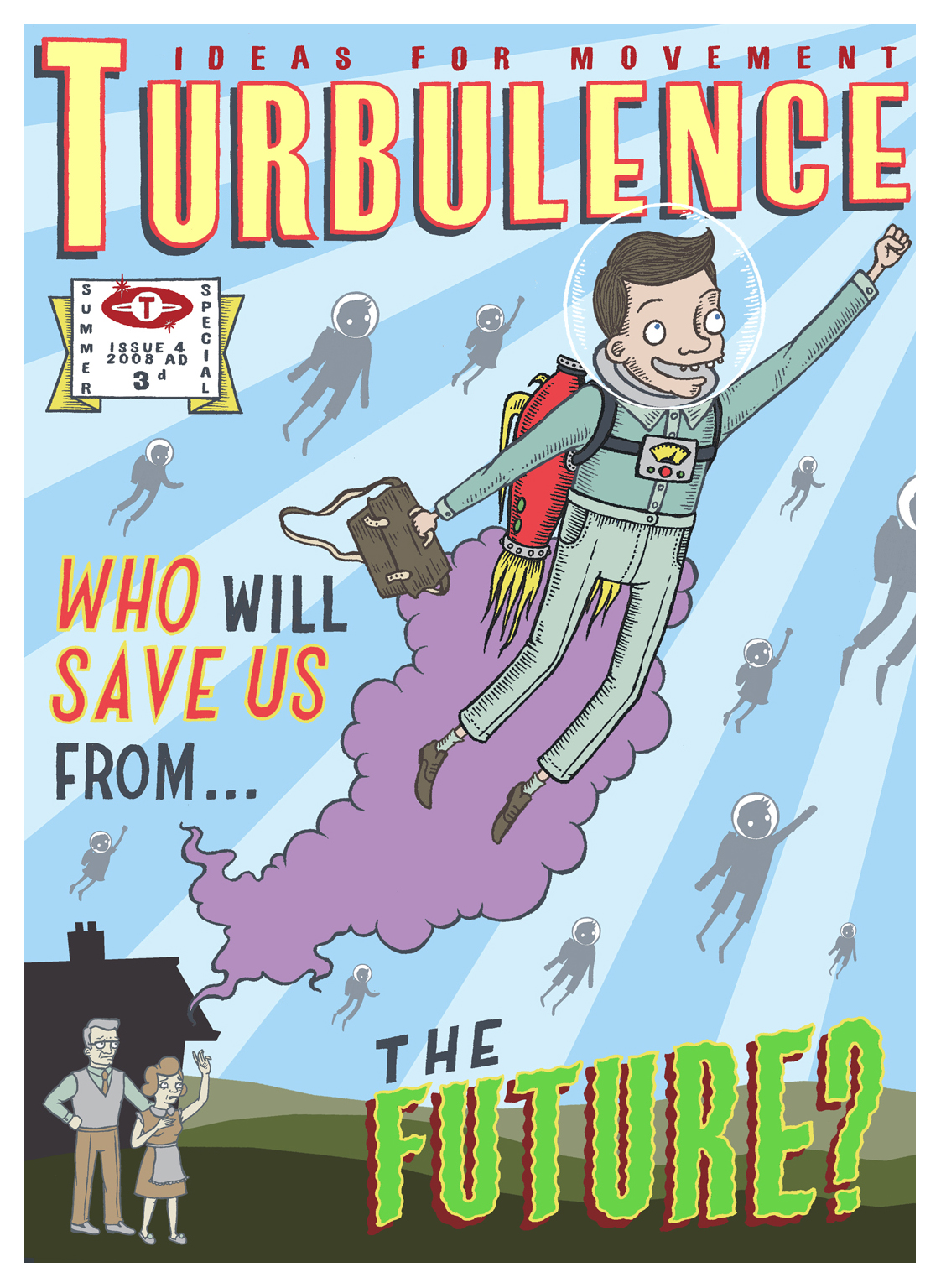

Will the upsurge in activity around climate change and the food crisis repeat the cycle of the movement of movements over the past decade – momentary visibility then dissolution? Harry Halpin and Kay Summer say ‘yes’, unless different models of organising are embraced.

“Then perhaps we would discover that ‘organisational miracles’ are always happening, and have always been happening.”

- Mario Tronti

How do we organise ourselves to achieve our political aims? It is an age-old question, with the answer often revolving around two poles of attraction, the centralised cadre versus the decentralised loose network. The centralised cadres are well-known: the classic political Party models from the Bolsheviks to the US neo-conservatives and even most trade unions are diverse in many respects but all have some organisational features in common: a tight core bound together by common ideology and a clear leadership structure. In contrast the decentralised network is a looser cluster of individuals, often with no coherent agreement on politics, who gather together based on affinity to take some form of action. This form was exemplified by the shut-down of the World Trade Organisation meeting in Seattle in 1999, and the emergence of the movement behind it. Of course, most political organisations mix aspects of both the centralised and decentralised models of organisation, balancing the benefits and problems of these two broad forms of organising. But this is usually the lens through which our debates and subsequent actions are viewed.

Let’s take a recent historical example. Almost ten years ago, protests at global summits in Seattle, Genoa and elsewhere pushed resistance to the project of neo-liberalism centre stage. New spaces to discuss moving beyond ‘summit hopping’ were formed, the ‘social forums’. Heated debates pitted what became known as the ‘horizontals’, those who distrusted hierarchy and pushed for this movement of movements to be a flat decentralised network, against the ‘verticals’ who wanted lines of authority so political demands and action plans could be decided and stated with clarity and the apparent ‘weight’ of large numbers of people. Both tendencies have benefits and problems: cadres have the ability to take action very quickly and can project a strength far greater than their numbers, while they inevitably fail when their ‘leadership’ is either disabled or stops acting in the best interest of the network. Decentralised networks of groups or individuals have benefits of wider participation, because they need less political agreement. Yet this form of organising poses problems as well, for as soon as the issue that people coalesced around is resolved, or appears less relevant, the informal ‘leaders’ disappear; or as the wider movement loses momentum, the decentralised network as a whole dissolves, and so loses its ability to co-ordinate action and move beyond the set of conditions that caused the loose network to coalesce in the first place. With hindsight, neither idealised form succeeded, nor some amalgam of the two. How do we know they didn’t succeed? Unfortunately today this movement rarely acts with the life it once had; the ritualised summit spectacles and social forums appear less relevant with every new cycle. Both tendencies failed to keep experimenting and innovating as they began to move the world, and so in turn the world moved onwards without them.

Can we break this lens through which we see political organising? Can we stop these two extremes, these poles of attraction, pulling us in two directions? Several have tried before. The Zapatista Army in Chiapas, Mexico, has been instrumental in altering our perceptions of political organising, but given their historical lineage from a guerrilla army with their own territory in areas remote from state control, their unusual situation has had limited impact on changing our views on concrete organisational problems. The other major attempt has been to invoke the concept of the ‘multitude’, outlined by Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt in Empire. Yet this too has broadly failed to alter our view on organising, because the multitude remains a vague and ill-defined term, often used almost mystically: with globalisation there is no ‘outside’ of capitalism, and therefore all resistance to it is similarly globalised into a linked-together ‘multitude’. We can all see ourselves as part of the multitude, yet still argue as either ‘verticals’ or ‘horizontals’ about what we do politically today or tomorrow. The multitude is, to us, more metaphor than tool. So we take a different, complementary, approach. We analyse the organisation of successful complex networks that may be analogous to the kinds of complex networks that our political organisations tend to become. By doing this we hope to clarify what general principles define a well-functioning network. Then we can seek to implement these general principles to confer similar desirable traits in our political networks. It’s time to learn what we can from the science of networks.

We can analyse the structure of things as diverse as political parties, natural ecosystems, trade unions, decentralised networks of political groups and individuals, the world’s financial architecture, and the internet, if we recognise that they are all essentially networks. A network consists of connections between otherwise disparate elements, which are called the nodes of the network. The architecture of these connections – exactly which node is connected to which other node – determines the structure of the network, and these structures can vary immensely. In a social movement setting, nodes could be of different types, which might be individuals, groups, social centres and websites. Within the movement of movements, the verticals and the horizontals, the parties and the loose collectives are all networks. They all have connections of otherwise disparate elements.

Moving up a level of abstraction, mathematical descriptions of different networks can help us to understand the similarities in architecture across very different sorts of networks. Simple characteristics such as the number of connections per node can be quantified, and shown to lead to different ‘distributions’ or spreads of network architecture. Moving beyond traditional political networks, understanding networks like ecosystems allows us to look at what characteristics render a network robust in the face of an attack. This is because ecological networks have survived eons of change — continental drift, climate fluctuations, and the arrival of new species — so any constancies in structure provide clues about which characteristics of complex networks correlate with a high degree of longevity in a changing world. In addition, ecosystems are a byword for efficiency, as the flow of energy through ecosystems has been honed by millions of years of evolution. The world’s financial architecture may also prove useful to study: not only is it a human-made artefact, but it has been successfully evolving for over 500 years and today spans the globe (of course, whether or not it survives another century is an open question). What we need to explain is what unites these ‘successful’ networks.

In any network, some nodes are more connected than others, making them ‘hubs’. This is a recurring pattern in the evolution of successful networks, ranging from the world wide web to many natural ecosystems. A ‘hub’ is not just a node with a few more connections than a usual node; a hub has connections to many other nodes – many quite distant – and also connects many disparate nodes (nodes of very different types). If you were to count all the connections each node has, you would get a mathematical distribution called a ‘power-law’ distribution with relatively few hyper-connected nodes – hubs – and a ‘long tail’ of less connected nodes. This is quite different from any egalitarian ‘levelling’ that leads to a ‘flat’ distribution, as well as from the ‘normal’ distribution where the majority of the distribution is clustered in the middle, forming the well-known ‘bell’ curve. It’s also different from a ‘centralised’ model of connections where everyone is connected only to a few nodes and not to their neighbours, which results in the ‘exponential’ distribution. Figure 1 (not shown here) shows the difference between the power-law and ‘normal’ (‘random’) distributions graphically. The power-law distribution is what results in both a long tail and hubs.

Unlike networks that have a normal or random distribution of connections, networks that have a power-law distribution of connections are ‘scale-free,’ which means that no matter how many more nodes are added to the network, the dynamics and structure remain the same. This seems to be a sweet spot in the evolution of networks for stability and efficiency. The network can get bigger without drastic changes to its function. Figure 2 (not shown here) gives a graphic representation of a ‘scale-free’ network.

The network theorist Albert-László Barabási uses the metaphor of height to understand a power-law distribution. Imagine that the amount of connections you had in a network influenced your height, so the more connections you had, the taller you would be. In the real world, average height does not vary that much: there are a few short people and a few tall people, with the rest clustered around the middle. If height followed a power-law distribution, the vast majority of people would be in the ‘long tail’ and have the same height, but a few people would be thousands of feet tall!

The question is: why do successful networks evolve these hubs, these few very densely connected nodes? Hubs are useful for the survival of a network since they allow distant local clusters of the network to be connected. Imagine sending a letter from London to Japan through a centralised postal network. All letters would have to go through one routing hub in, say, New York, and this single hub would be vulnerable to overloading. It’s also not very efficient – sending a letter from London to Paris would have to be routed through New York! Now imagine sending the letter through a network that consisted only of dense, local connections with no hubs, a totally decentralised network – it would take a long time, since the message would have to hop from one small connection to another. However, in a network with several hubs, you’d have direct long-distance connections from London to Mumbai to Japan that are in turn coupled with local connections, so the message would arrive quickly and be less prone to disruption (if London to Mumbai were down, London to Beijing and then to Japan would do just as well). Hubs allow everyone to be connected to everyone through a few short steps – the ‘small world’ effect. Now replace the idea of a letter travelling through the postal system with patterns of behaviour, tactics, strategies, and it should be clear that hubs are useful for political networks.

In the context of the celebration of ‘horizontality’ that characterised the emergence of the alterglobalisation movement, some consider the evolution of hubs per se to be a sign of centralisation, and therefore tend to try to avoid them. Others might want control of a single hub and so they sabotage emerging hubs as potential competitors, a tendency that was all too visible in the UK anti-war movement. Both sets of fears are wrong: successful networks almost always naturally evolve several or many important hubs. If you were to compile a list of the most popular internet sites, you’d notice a few of them (Google, Yahoo, eBay) have the vast majority of the connections, while most sites have just a few. Note the redundancy: Google does the job of Yahoo, and vice versa. There is no one omnipotent leader. Nothing is indispensable. This pattern is not just repeated across the internet – it applies across a remarkably diverse set of systems, ranging from human languages to social networks of sexual promiscuity, as well as ecological and financial networks. In each we find a small number of highly-connected nodes, many less-connected nodes, and massive redundancy. These recurrent patterns across diverse networks tell us something about the characteristics our social movements need to evolve to have robust, efficient and effective networks.

Politically, hubs are easy to spot. There seem to be a few people in every network who do a vast amount of the work, a few people with connections seemingly everywhere. In our experience across quite diverse political movements, people exert a good deal of effort trying to suppress new hubs because they view them as signs of centralisation, or because they wish to maintain their own status as ‘hubs.’ However, the evolution of new hubs appears to be a hallmark of maturity in long-lasting networks. And of course hubs don’t have to be people, but can be places, like social centres, and events, like the protests at world summits and ‘social forums’.

There is a looming contradiction: how can we have hubs and still have a strong network of dense connections that is not dependent on them? Don’t hubs lead to the emergence of permanent, entrenched leaders, centralisation and other well-documented problems? There is something of a tension here: the point is not simply that we should develop hubs, but that we have to simultaneously ensure that the hubs are never allowed to become static, and that they’re at least partially redundant. Sounds complicated, but healthy and resilient networks aren’t characterised simply by the presence of hubs, but also by the ability of hubs to change over time, and the replacement of previous hubs by apparently quite similar hubs. Think about search engines on the web: Google wasn’t always a key hub – once upon a time that role was played by Alta Vista, Lycos, and others whose names are now forgotten.

While the presence of some hubs helps a network, a single or even a few hubs by themselves are a liability unless local connections are dense and new hubs are emerging in the rest of the network. The fact that a single node is not connected to a huge number of other nodes does not mean it is not important for the health of the network. Far from it, for it is precisely the density and power of the connections of the nodes in the ‘long tail’ that are the ‘heart’ of the network: taken together, their connections far outweigh the impact of the key hubs combined.

The long tail does not drop off into nothingness (which would be the ‘exponential’ rather than ‘power-law’ distribution), where there are a few hubs and every other node has almost no connections. Instead, the long tail is extensive, consisting of small groups of dense connections, going ever onwards. In fact, the vast majority of the connections in the network are not in the hub, but in the long tail. One clear example is that of book-selling in the 21st century: the majority of Amazon.com’s book sales are not in the best-seller list, but in those millions of titles in the long tail that only a few people order. Every successful movement must be built on dense local connections. It is these dense local connections that support the dynamic creation of hubs.

In a perfect world, every node would be a hub – we would all easily connect with any other person and be able to communicate. However, creating connections takes time and energy, so nodes that are more long-standing or just have more spare time will naturally become hubs. This isn’t rocket science: people who have been involved in social movement networks longer tend to become the most well-connected, as do people who have more time to spend on the cause of the network, such as people who have escaped working full-time. Of course, few people can escape working full-time forever, and few remain indefinitely involved. How can a social movement not be dependent on any one particular hub, or set of hubs? The answer appears to be a matter of existing hubs actively supporting the long tail, encouraging new people to in turn become hubs, by introducing them to other connections, and never forgetting that everyone should be encouraged to be as locally connected as possible. A successful network has both a dense long tail, with as many hubs as possible that collectively and redundantly span the entire network, and hubs whose massive number of connections bridge otherwise disparate parts of the network.

Hubs tend to evolve naturally in well-functioning networks – but we can accelerate the process of network development. Unfortunately people can’t become hubs without largely re-inventing the wheel. It might be irritating for existing hubs, but it’s true. Being a hub requires more than just introductions, it requires information, skills, knowledge, and a memory of the past. However, we can accelerate this process by decentring as much of the connections and knowledge as possible away from individual humans and onto the environment, whether this environment be books, websites, songs, maps, videos, and a myriad of yet un-thought-of representational forms. A useful example is the pheromone trace of the ant, reinforced as more ants use a particular trail. The mere act of ‘leaving a trail’ shows how individuals with limited memory can use the shaping of the environment as an external memory. You can imagine this on an individual level: a person using their mobile phone to remember the phone numbers of their friends. With easy access and reliability, the phone almost seems part of your intelligence. Just extend this so that the part of your mind that is extended into the environment is accessible and even modifiable by other people, and collective intelligence begins.

The human equivalent of the pheromone trace is nothing less than ‘culture’ itself. Most aspects of culturally embedded collective intelligence in the environment, ranging from the evolution of cities to Wikipedia, allow us to navigate the world around us, a world formed collectively by those treading paths before us. This use of the environment to store collective intelligence allows for the easier creation of hubs. It has a number of advantages over direct individual-to-individual communications, as there is no need for simultaneous presence, so interaction can be asynchronous, and individuals can even be anonymous and unaware of each other. Collective intelligence allows highly organised successful actions to be performed by individuals who, with limited memory and knowledge, would otherwise be unable to become hubs. So when a hub is destroyed – for example when an individual leaves the network – a new hub can be equipped with knowledge as soon as possible.

Over the last decade, some of the currents of the global movements, particularly those in the global North, have been radically deficient at producing collective intelligence, leading to a genuine gap in passing knowledge and abilities to the influx of people engaged in the politics of climate change and the food crisis. Collective intelligence requires a commons of collective representations and memory accessible to the network, and so digital representations on the internet are ideal. Indymedia was a step towards this type of collective intelligence for many of these currents, but its focus on ‘reporting’ rather than analysis has reduced its use as a mechanism for passing on knowledge. Again, this seems to have arisen because of a misplaced fear of hubs.

A key focus for improving our collective intelligence would be a few central websites compiling analyses of social movements and events, alongside practical pieces from key hubs and organisers on how particular events were pulled off. A collective ratings approach would allow people to quickly find needles in the electronic haystack, via Digg-It-style ‘I like this article’ tags, or collaborative bookmarking, allowing different users to see each other’s bookmarked webpages. Of course some of these types of things exist, with tagging systems well developed on sites of magazines, newspapers and blogs. However, no current website performs the function of an analysis and learning hub, as Indymedia does for news. There are other effective technologies for creating collective intelligence, such as wikis for text editing and textmob for coordinating street action, but much work needs to be done to develop, explore and deploy these tools.

While struggles wax and wane, it is clear that the gloriously misnamed ‘anti-globalisation’ movement is declining while a new movement, which we call the ‘climate change’ movement is growing. Both can be considered separate moments in a greater ‘movement of movements’. The question of climate change gives relatively fixed time-constraints before we reach various ‘tipping points’ in the Earth’s climate system – major sea-level rises displacing cities and their inhabitants, droughts making agriculture difficult, and so on – which most of humanity will find difficult or impossible to adapt to. Perhaps this realisation will allow us to move beyond organisational panic and tired arguments over centralised and decentralised models of organising, and ground our organisational experiments in studies of existing and successful networks. If we are to act swiftly and sustain momentum we will need to create collective intelligence – the ability to create accurate records of events, distribute them widely, analyse success and failure, and to pass on skills and knowledge. This is what the emerging climate change movement must aggressively focus on.

Nobody knows the precise dynamics of what actions will change the world, but we do know that any social movement will fail to head off catastrophic climate change if it sticks solely to the politics of climate change. With food riots on three continents and spiralling energy costs worldwide, changes in the weather are taking a backseat to basic questions of people getting the food and energy they want. These crises are sign-posts to the defining issues of international solidarity and justice in the 21st century: how does humanity allocate finite resources globally? The reason is simple: scientist Jared Diamond has calculated that the average amount of food, energy, metal and plastic consumption by an individual in Western Europe and the United States is approximately thirty-two times that of an average individual of the rest of the planet. Simple maths shows that as the rest of the world moves towards resource use levels that mirror average levels in the UK, US and Germany, this would use the resources equivalent to a global population of 72 billion, against a current world population of almost 6.5 billion. This isn’t physically possible – even the most frenzied capitalist would run out of world to exploit – so something fundamental must shift.

Some, seeing millions of people getting on planes, into boats, or walking to the global North every year, will call for the shift to be to even more xenophobic border control policies. Others, seeing the life-system-threatening impact of such resource depletion, will welcome a ‘khaki-green’ or eco-fascist authoritarian state. These symptoms of the general structural instability of capitalism will increase with time: there is now a brief window of opportunity – a moment outside ‘normal’ time – where a network of social movements can actively form and radically reshape the world. To do so successfully, future movements must consciously try to avoid two distinct fates: either the dissolution into a decentralised network of loose clusters of relatively isolated groups, movements and individuals – the fate of the summit-hopping phase of the movement of movements – or a decline towards a centralised network of cadres, which severely damaged the movement in the Sixties. Our lines of flight from these dead-ends consist in wilfully pushing ourselves to learn from successful networks and evolve towards a mature distributed network with abundant hubs and a powerful long tail: a movement with both mass participation and dynamic hubs of people and events, capable of evolving and responding rapidly to a fast-changing world. A tall order – perhaps – yet the alternative is bleak indeed.

Key messages for political networks

• Encourage people to become hubs

• Develop other hubs, with dense connections to lots of distant nodes

• Hub redundancy is important – don’t worry about duplicating functions

• Let hubs evolve

• Focus on the long tail: have more limited interactions with the greatest number of people and places

Harry Halpin and Kay Summer have both had longtime involvement in the movement of movements and some of its precursors. They earn their wages by doing scientific research, some of which involves trying to better understand network organisation. You can get in touch with the authors at harry@j12.org and kaysmmr@yahoo.co.uk.

No comments:

Post a Comment